MongoBleed explained simply

CVE-2025-14847 allows attackers to read any arbitrary data from the database's heap memory. It affects all MongoDB versions since 2017, here's how it works:

MongoBleed, officially CVE-2025-14847, is a recently-uncovered extremely sensitive vulnerability affecting basically all versions of MongoDB since ~2017.

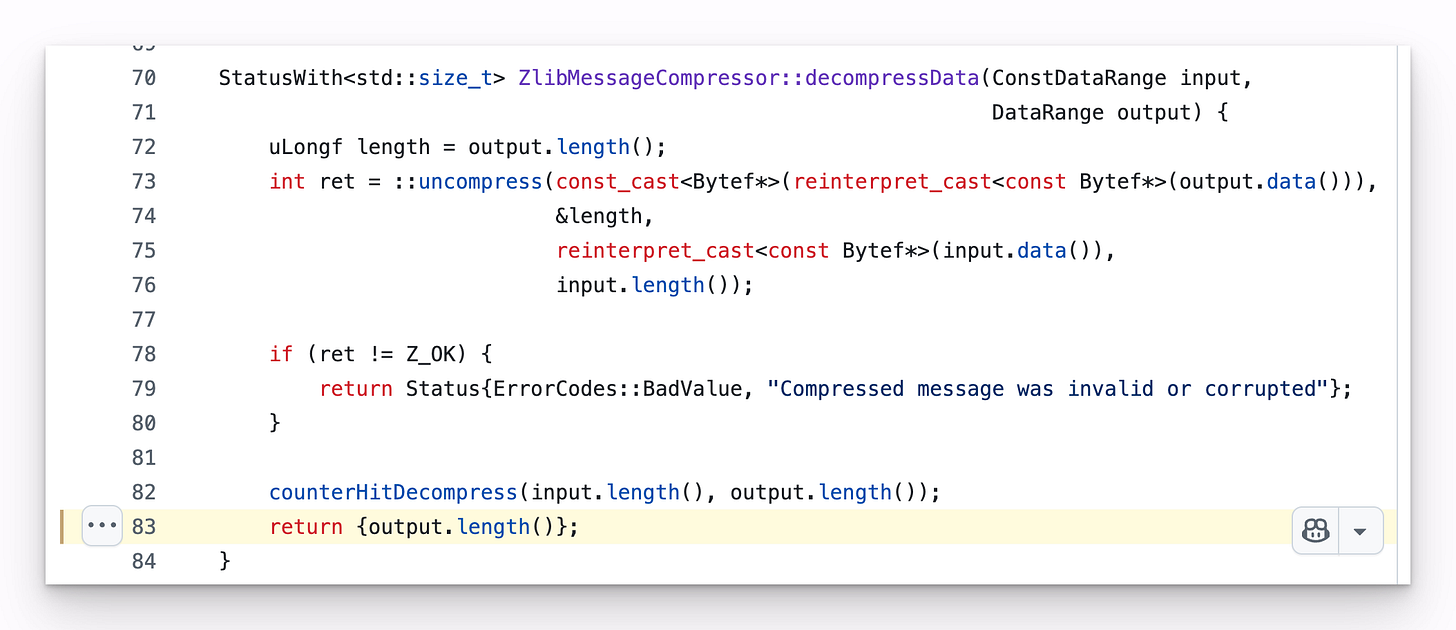

It is a bug in the zlib1 message compression path in MongoDB.

It allows an attacker to read off any uninitialized heap memory, meaning anything that was allocated to memory from a previous database operation could be read.

The bug was introduced in 20172. It is dead-easy to exploit - it only requires connectivity to the database (no auth needed). It is fixed as of writing, but some EOL versions (3.6, 4.0, 4.2) will not get it.

MongoDB Basics

Let’s get a few basics out of the way before we explain the bug:

MongoDB uses its own TCP wire protocol instead of e.g HTTP. This is standard for databases, especially ones chasing high performance.

Mongo uses the BSON format for messages3. It’s basically binary json but with some key optimizations. We will talk about one later because it is essential to the exploit.

Mongo doesn’t have endpoints or RPCs. It only uses a single op code called OP_MSG.

The OP_MSG command contains a BSON message. The contents of the message denote what type of request it is. Concretely, it’s the first field of the message that marks the request type. 4

The request can be compressed. In that case, an OP_COMPRESSED message is sent which wraps the now-compressed OP_MSG BSON.

The request then looks like this:

OP_COMPRESSED message

┌────────────────────────────┐

│ standard header (16 bytes) │

├────────────────────────────┤

│ originalOpcode (int32) │

│ uncompressedSize (int32) │

│ compressorId (int8) │

│ compressed OP payload │

└────────────────────────────┘Critically, the

uncompressedSizefield denotes how large the payload is once it’s uncompressed.

Exploit Part 1

The first part of the exploit is to get the server to wrongfully think that an overly-large OP_MSG is coming.

An attacker can send a falsefully large `uncompressedSize` field, say 1MB5, when in reality the underlying message is 1KB uncompressed.

This will make the server allocate a 1MB buffer in memory to decompress the message into. This is fine.

The critical bug here is that, once finished decompressing, the server does NOT check the actual resulting size of the newly-uncompressed payload.

Instead, it trusts the user’s input and uses that as the canonical size of the payload, even if it got a different number.6

The result is an in-memory representation of the BSON message which looks something like this:

[ 1KB of REAL DATA | 999KB of UNREFERENCED HEAP GARBAGE ]

↑ ↑

actual length (1KB) user input length (1MB)Unreferenced Heap Garbage

Like in every programming language, when a variables in the code goes out of scope, the runtime marks the memory it previously took up as available.

In most modern languages, the memory gets zeroed out. In other words, the old bytes that used to take up the space get deleted.

In C/C++, this doesn’t happen. When you allocate memory via `malloc()`, you get whatever was previously there.

Since Mongo is writen in C++, that unreferenced heap garbage part can represent anything that was in memory from previous operations, including:

Cleartext passwords and credentials

Session tokens / API keys

Customer data and PII

Database configs and system info

Docker paths and client IP addresses

[ REAL BSON DATA | password: 123 | apiKey: jA2sa | ip: 219.117.127.202 ]Exploit Part 2

Now that the server has wrongfully allocated some potentially-sensitive data to the input message, the only thing left for the attacker is to somehow get the server return the data.

BSON

As mentioned, BSON is Mongo’s way of serializing JSON. As mentioned on its site, it was designed with efficiency in mind:

3. Efficient

Encoding data to BSON and decoding from BSON can be performed very quickly in most languages due to the use of C data types.

C Strings

C famously uses null-terminated strings7. A null-terminated string means that a null byte is used to mark the end of the string:

char* s = "hello"

// in memory, this is represented as an array of characters with the last element being the null terminator: h e l l o \0The way such strings get parsed is very simple - the deserializer reads every character until it finds a null terminator.

Malicious BSON Input

If you recall, I said earlier that the first field of the BSON message denotes what type of “RPC” the command is.

As such, the first thing a server does when handling an incoming message over the wire is… parse the first field!

Because fields are strings, and strings are null-terminated CStrings, the deserializing logic in the MongoDB server parses the field until the first null terminator found.

An attacker can send a compressed, invalid BSON object that does NOT contain a null terminator. This forces the server to continue scanning through foreign data in the wrongly-allocated memory buffer until it finds the first null terminator (\0)

# Conceptual

[ REAL DATA | UNREFERENCED HEAP GARBAGE ]

# Practical Example

[ { "a | password: 123\0 | apiKey: jA2sa | ip: 219.117.127.202 ]As the first null terminator is right after the password, the server would now think that the first field of the BSON is:

"a | password: 123"Obviously that is an invalid BSON field, so the server responds with an error to the client. In order to be helpful, the response contains an error message that shows which field was invalid:

{

"ok": 0,

"errmsg": "invalid BSON field name 'a | password: 123'",

"code": 2,

"codeName": "BadValue"

}Boom. The attacker successfully got the server to leak data to it.

Any serious attacker would then run this over and over again, thousands of time a second, until they believe they’ve scanned the majority of the database’s heap. They can then repeat this ad infinitum.

Impact

1. Ease of Exploitation - “Pre-Auth”

The impact of this is particularly nasty, because the request-response parsing cycle happens before any authentication can be made. This makes sense, since you cannot begin to authenticate a request you still haven’t deserialized.

This allows any attacker to gain access to any piece of potentially-sensitive data. The only thing they need is internet access to the database.

Exposing your database to the internet is a practice that’s heavily frowned upon8. At the same time, Shodan shows that there are over 213,000 publicly-accessible Mongo databases.

2. Eight Years of Vulnerability (handled questionably)

The PR that introduced the bug was from May 2017. This means that, roughly from version 3.6.0, any publicly-accessible MongoDB instance has been vulnerable to this.

It is unknown whether the exploit was known and exploited by actors prior to its disclosure. Given the simplicity of it, I bet it was.

As of the exploit’s disclosure, which happened on 19th of December, it has been a race to patch the database.

Sifting through Git history, it seems like the fix was initially committed on the 17th of December. It was merged a full 5 days after in the public repo - on the 22nd of December (1-line fix btw).

That beig said, MongoDB 8.0.17 containing the fix was released on Dec 19, consistent with the CVE publish data. While public JIRA activity shows that patches went out on the 22nd of December, I understand that Mongo develops in a private repository and only later syncs to the public one.

In any case - because there’s no official timeline posted, members of the community like me have to guess. As of writing, 10 days later in Dec 28, 2025, Mongo have still NOT properly addressed the issue publicly.

They only issued a community disclosure of the CVE a full five days after the publication of it. It is then, on the 24th of December, that they announced that all of their database instances in their cloud service Atlas were fully patched. Reading through online anecdotes, it seems like the service was patched days before the CVE was published. (e.g on the 18th)

Mongo says that they haven’t verified exploitation so far:

“at this time, we have no evidence that this issue has been exploited or that any customer data has been compromised”

3. Ease of Mitigation

Mitigation is admittedly very easy, you have one of two choices:

Update to the newest patch

Disable zlib network compression

I found the latter wasn’t circulated a lot in online talk, but I understand is just as good as a short-term mitigation.

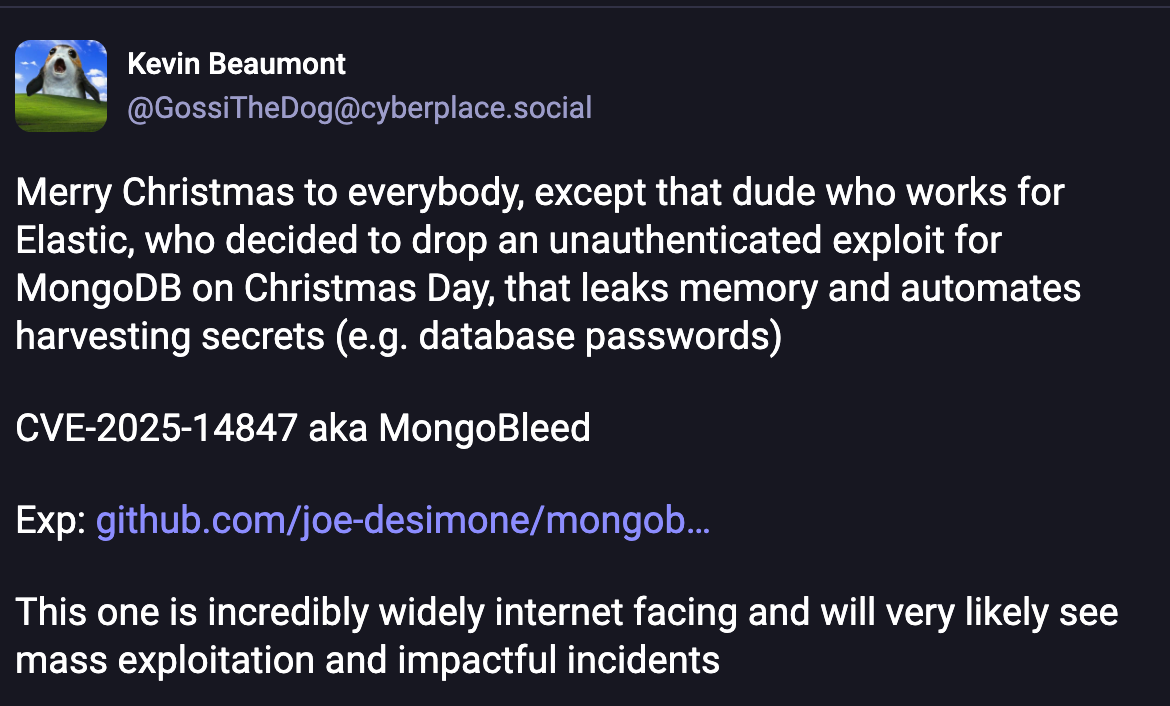

A bit of Drama?

The tech lead for Security at Elastic coined the name MongoBleed by posting a Python script that acts as a proof of concept to exploiting the vulnerability: https://github.com/joe-desimone/mongobleed

This is particularly interesting, because despite being different systems, Mongo competes with Elastic on Vector Search, Text Search and Analytical use cases.

Summary

The exploit allows attackers to read arbitrary heap data, including user data, plaintext passwords, api keys/secrets, and more.

It is performed by leveraging a simple, malformed zlib-compressed request.

MongoDB versions from 2017-2025 are vulnerable to this exploit.

Rough timeline:

June 1, 2017: Commit introducing the bug gets merged.

Dec 17, 2025: Code for the fix is written (original commit date).

(?) Dec 17-19, 2025: Code is merged to Mongo’s internal repo

(?) Dec 17-19, 2025: MongoDB Atlas cloud patched

Dec 19, 2025: CVE officially published.

Dec 22, 2025: Code with the fix is merged to the public repo.

Dec 24, 2025: MongoDB announce the patch, say all Atlas databases are patched.

On Dec 24th, MongoDB reported they have no evidence of anybody exploiting the CVE. Given the fact this exploit lived on for ~8 years and is extremely simple to both exploit and uncover… I am sure it was exploited.

MongoDB have not apologized yet.

edit: on Dec 29, they at least published something! (no sorry though, lol)

There are over 213k+ potentially vulnerable internet-exposed MongoDB instances, ensuring that this exploit is web scale:

Interesting Links

Official CVE: https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2025-14847 (Dec 19, 2025)

PR introducing the bug: https://github.com/mongodb/mongo/pull/1152 (May 2017)

Commit fixing the issue: https://github.com/mongodb/mongo/commit/505b660a14698bd2b5233bd94da3917b585c5728#diff-e5f6e2daef81ce1c3c4e9f7d992bd6ff9946b3b4d98a601e4d9573e5ef0cb07dR77

Security Report on the incident, including fix versions: https://www.ox.security/blog/attackers-could-exploit-zlib-to-exfiltrate-data-cve-2025-14847/

Write-up on how to detect exploitation attempts via log analysis: https://blog.ecapuano.com/p/hunting-mongobleed-cve-2025-14847

Somebody also vibe-coded a detector: https://github.com/Neo23x0/mongobleed-detector

Other Reads You May Like:

zlib is a library for compression. It uses the DEFLATE algorithm under the hood, but produces results in a specific wire format to ease sending such data over the wire. (e.g includes metadata like flags, checksums, etc)

Here is the PR that introduced it. I’m not aware of Mongo’s public review practices, but it appears as if nobody explicitly reviewed the change.

They actually created it. There’s a very good site for it - https://bsonspec.org/

Weird, I know. Here are examples of different commands, just so you get a sense:

Insert a document into the users table

{

"insert": "users",

"documents": [{ "name": "alice", "age": 30 }]

}Delete users with

inactive=true

{

"delete": "users",

"deletes": [ { "q": { "inactive": true }, "limit": 0 }]

}Check the server’s status

{ "serverStatus": 1 }I’m making this number up. There is probably some limit on the server side as to how large a request can be - perhaps 1MB is too large.

Here is the line (pre-fix): https://github.com/mongodb/mongo/blame/b2f3ca9c996ba409e7d48601fca16c28fd58b774/src/mongo/transport/message_compressor_zlib.cpp#L83

`output` is the large memory buffer that was allocated earlier

The code, instead, ought to return the referenced `length` field, as that gets updated with the actual length that was seen post-compression.

This has been the cause of many security issues in the past.

The most common comment I saw online is that you “deserved it” if you exposed your DB to the wild. 😁